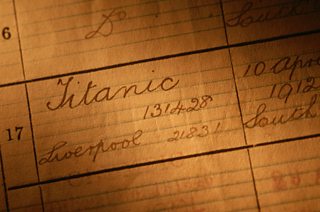

10 Mistakes that led to the Titanic Disaster

The sinking of the Titanic was a perfect storm of human error, technological overconfidence, and bad luck.

You can read more history articles .

The ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ is not responsible for the content of external websites.

1. A massive fire raged in the ship’s bowels in the days leading up to the disaster, potentially weakening the hull.

Around March 31st 1912, 10 days before Titanic embarked on its maiden voyage, a fire broke out in Coal Bunker 6. Fires like this were common in the steamship era and often occurred due to spontaneous combustion. As strange as it sounds, the protocol was not to extinguish the fires, but to shovel the burning coal out and feed it into the ship’s boilers. This is exactly what the crew of the Titanic did and the fire continued to burn right up until April 14th - just one day before the ship sank. Did the fire have anything to do with the hull breach? Maybe. Smouldering coal can reach temperatures of up to 1000℃ — and steel exposed to such heat can lose 40% or more of its strength, which could explain how the iceberg was able to tear through Titanic’s hull so easily.

2. The crew did not have access to the ship’s binoculars.

Famously, the lookouts in the crow’s nest the night Titanic sank were using only their naked eyes to try and spot icebergs. You might assume this was because the ship didn’t have binoculars, but you’d be wrong. Titanic was absolutely equipped with binoculars — the crew just didn’t have access to them. The day before the Titanic set sail, the ship’s second officer, David Blair, was unexpectedly reassigned. Due to the haste of his departure, Blair accidentally took the key to the crow’s nest locker with him.

3. Three missing letters led to a vital warning being missed.

The Titanic was equipped with the most advanced Marconi wireless machines on the market, meaning it could communicate with ships up to 900 miles away in peak conditions. On April 14th, 1912, the night Titanic struck the iceberg, the ship’s wireless operators received at least six iceberg warnings. Many of these were relayed to Captain Smith. But at 9:40 pm Titanic received its most vital message yet from the SS Mesaba. It read: “Saw much heavy pack ice and great number large icebergs. Also field ice” This was a clear warning that they were headed directly into an extremely dangerous area of the ocean, but the message never reached Captain Smith because it was missing the vital “MSG” prefix. “MSG” stood for “Master Service Gram” and signalled to wireless operators that the message was urgent and meant to be given directly to the captain.

4. A wildly out-of-date safety regulation led to disaster.

That the Titanic carried a wildly insufficient number of lifeboats is well known. While it’s easy to assume that the White Star Line was simply being irresponsible, they were actually operating well within the regulations set forth by the British Board of Trade. In fact, they provided more boats than were legally required. In 1894, the British Board of Trade determined that sixteen 70-person lifeboats were sufficient for large vessels like the Titanic (the Titanic carried twenty). The problem was that at the time this regulation was made, the largest ships weighed around 10,000 tonnes — the Board of Trade didn’t account for how quickly shipping would advance and by 1912 vessels had exploded in size. Titanic weighed a whopping 46,329 tonnes, nearly five times more than the shipping regulation was designed for.

5. Overconfidence and complacency

While the White Star line followed safety regulations in the strictest sense, it still doesn’t explain why they didn’t adjust the number of lifeboats on board to match the ship’s size. After all, they certainly knew that twenty lifeboats could only accommodate about half the ship’s passengers and crew. So why weren’t they more prepared?

Well, it’s important to remember that the Titanic was thought to be virtually unsinkable. “It had safety features which were cutting edge,” explains Titanic expert Susie Millar. The ship was equipped with a double-bottomed hull and 16 watertight compartments designed to keep it afloat in the event of an accident. For this reason, the White Star Line never envisioned that the lifeboats would need to be used to evacuate the entire ship. Rather, they saw them as a means to ferry passengers onto rescue vessels, meaning each lifeboat would make multiple trips.

Furthermore, transatlantic travel was considered extremely safe. Accidents were rare. “I think everybody by 1912 was fairly complacent about the safety of transatlantic travel,” says Dr. Stephanie Barczewski, author of Titanic: A Night Remembered. “There had not been a major accident for a long time [and] everybody had great faith in the ability of these ships.”

6. Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the White Star Line, may have pushed the Captain to go faster

The United States Senate held several inquiries into the sinking of the Titanic after the disaster. At one of them, first-class passenger Elizabeth Lines testified that she overheard Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the White Star Line, discussing an increase in the ship’s speed with Captain Smith. Lines claimed that Ismay told the Captain: "We will beat the Olympic and get into New York on Tuesday." This has been interpreted by many to mean that the chairman was pressuring Captain Smith to beat the Atlantic crossing record held by Titanic’s sister ship the Olympic. If true, Ismay was putting thousands of lives at risk for the sake of public esteem and corporate profit. When the Titanic struck the iceberg it was travelling at around 22.5 knots - very close to its top speed of 23 knots. If it hadn’t been going so fast, it could have had more time to avoid the iceberg and the force of impact would not have been as great.

There is, however, reason to doubt this claim. Ismay was one of only around 20% of male passengers who survived the Titanic. Because of this, he was pilloried in the press and painted as a rich, out-of-touch, coward who snuck onto a lifeboat with the women and children instead of going down with the ship like a gentleman. This bias could have led people to interpret Lines’ testimony in the harshest possible light.

7. Swerving to avoid the iceberg directly led to it sinking.

When the iceberg was finally sighted at 11:40 pm, First Officer William Murdoch made what sounds like a very logical decision: swerve to avoid it. However, this one action proved to be catastrophic.

“There were 9000 other ways that it could have hit the iceberg, and it would have been fine.” explains Professor Stephanie Barczewksi author of Titanic: A Night Remembered “It would've done damage to the ship, and it probably would've killed some people, but it wouldn't have had the incredibly catastrophic result that it had. It had to hit that iceberg in exactly the right way, scrape along it [...] at the precise angle right to put that kind of damage into the ship.”

If Murdoch had realised that there was no way to avoid the iceberg and instead hit it head-on, thousands of lives would have been saved. “Titanic was designed to survive that kind of collision,” Barczewski continues, “He would have crumpled the bow, he probably would have killed 200 people in the front of the ship [...] but the ship would have survived.”

8. The Captain cancelled a vital safety drill the day the Titanic sank

April 14th, 1912 was a Sunday. Had it been any other day of the week, the lifeboat safety drill set to take place that morning might have gone forward. But, according to some accounts, Captain Smith cancelled it because it would interfere with church services.

This, as it turned out, was a fatal error.

When the passengers were finally told to head to the lifeboats around midnight, chaos ensued. Most of the crew had no experience lowering lifeboats and were unfamiliar with the lowering mechanisms. Some boats almost fell off their davits and others were lowered at such high speeds that they nearly capsized. Overall, the process of launching the boats took much longer than it should have, costing precious time as the ship began sinking at an alarming rate.

9. The “Women and Children First” rule was grossly misunderstood by the ship’s officers.

When it became clear that the Titanic was sinking, Captain Smith ordered Second Officer Charles Lightoller and First Officer William Murdoch to begin loading women and children into the lifeboats first. This was a well-known maritime tradition, not a set regulation, and how it was executed was up to the discretion of individual officers. Lightoller, who was charged with the portside evacuation, enforced it strictly, only allowing women and children onto the boats even if there was room for men to board. Many of the boats on the portside left only half full, resulting in hundreds of unnecessary casualties.

Over on the starboard side, Murdoch was far more lenient. He still allowed the women and children to get on the boats first, but once they’d boarded safely their husbands and fathers could join them. Unlike Lightoller who seemed to prioritise honour and maritime tradition, Murdoch’s priority was to get the lifeboats launched as quickly as possible.

“What we find is Murdoch, who's actually allowing men to go in lifeboats with women and children, that allows families to load boats very, very quickly.” explains Tim Maltin, author of 101 Things You Thought You Knew About the Titanic “Whereas Lightholler on the other side of the ship was splitting up families, which is taking a long time and causing a lot of people to reject getting in a boat at all.”

10. The nearby SS Californian (mistakenly) ignored the Titanic’s distress calls.

The SS Californian, a cargo ship, was positioned just 10 miles away from the Titanic when it sank. It could have easily gotten to the floundering vessel in time to save hundreds if not thousands of lives, but due to miscommunication, the SS Californian missed the Titanic’s distress calls.

At 11:07 pm on April 14th 1912, the Californian’s wireless operator, Cyril Evans, sent a message to the Titanic informing them that they were “stopped and surrounded by ice.” But because the Californian was so close by, the message came through Jack Phillips, the Titanic’s wireless operator’s headset at a deafening level. In response, a frustrated and tired Phillips replied “Shut up, shut up. I am busy working Cape Race.” So, Cyril Evans decided to go to bed for the night — missing the Titanic’s frantic distress calls when it struck the iceberg just thirty minutes later.

At around 12:45 am, Second Officer Lightoller ordered the crew to begin firing distress rockets to signal nearby ships. The problem was these rockets were white — the standard colour for ship-to-ship communication. Therefore, the crew of the Californian misinterpreted the Titanic’s rockets as routine company signalling and ignored them.

More from the ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½

-

![]()

Not Just The Tudors

From the Aztecs to witches, Prof Suzannah Lipscomb talks all aspects of the Tudor period

-

![]()

D-Day: The Tide Turns

D-Day: The Tide Turns follows the real people involved in the Normandy Landings.

-

![]()

Tortoise Investigates: Pig Iron

A story about the mysterious death – and life – of a young war reporter on the frontline.

-

![]()

The Rest is History

Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook are interrogating the past to de-tangle the present.