Why lying is human nature

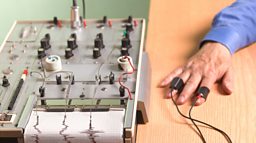

It might seem strange to think of lying as normal and not cheating – even in an age of fake news - but both humans and animals have some instinctive reasons why they might want to mislead others.

Ella Al-Shamahi speaks to Dr Roman Stengelin of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and professional poker player Liv Boeree to discover why lying has a role to play in the natural world.

Here are eight things we found out about lying:

It’s rare

A study of 1000 American adults asked them to count their lies over a 24-hour period. Nearly 60% didn’t lie at all. Of course, as Ella observes, “it was only one day … and how much can you really trust the liars to tell the truth about their lies?”

It starts early

Evolutionary anthropologist Dr Roman Stengelin investigates children from very different cultures to discover when and how they develop the ability to lie. Using a tabletop game involving sweets, he found that in both industrialised and non-industrialised societies, children have started to understand how to manipulate those around them by the age of four.

It's universal

Dr Stengelin’s studies lead him to believe that lying is “a very good candidate for a human universal,” adding: “I think biology and culture is always at the table with those questions. But I think it is something that's very fundamental for human psychology for sure.”

People across the globe tell each other stories, and the role of the trickster or the deceiver, is something that is found almost everywhere.Dr Stengelin on lying being universal

One example Dr Stengelin uses to illustrate the nurture side of the equation is storytelling. “People across the globe tell each other stories, and the role of the trickster or the deceiver, is something that is found almost everywhere, I think.”

It has international variations

The same US study that recorded lies within a 24-hour period, researchers found that there were international variations in the amount of lying. “China had the same rate as the States,” notes Ella, “but in Kenya, the number of people who admitted to lying was twice as high.” However, once again, the findings were based on self-reporting because, as Ella points out “that’s cheaper.”

It depends on group vs individual perspective

Another international study discovered a different mindset was in play when it came to lying for a positive gain or outcome. Involving Canadian and Chinese children, the study showed that their broad national societal characteristics bore out when it came to lying. Canadian children were positive towards telling lies to benefit the individual, while Chinese children saw lies to benefit the group as more favourable.

It has an adaptive value

Because there is a moral judgement against lying, Ella asks Dr Stengelin why we haven’t evolved to be honest?

“There's a very obvious adaptive value to deceiving others,” Dr Stengelin responds, “I just think that has to be because there are so many benefits from manipulating minds. If we go out for a hunt, for example, we'll try to deceive the other animal in order to make them do what we want them to do. So, deception is not just a thing between humans, it's something that we use to not only navigate us, but also life more generally.”

It has a positive value

Lying is typically associated with anti-social behaviour, but some lies have quite the opposite effect. For example, there are “white lies”, where someone’s feelings are spared from any perceived embarrassment. Clear examples of this can be found in a study called ‘Children tell white lies to make others feel better’ where children aged seven upwards were found to tell white lies to their peers if their classmates were sad about a piece of artwork they made. There are also “pro-social” lies that, more than consoling others, are designed to actively uplift them and, says Dr Stengelin, “have a bit of a social glue function in society.”

Sometimes, it’s the name of the game

There are times when lying is absolutely what is expected, as professional poker player Liv Boeree well knows. “The actual rules of the game demand that you have some degree of bluffing,” she says, “and the real sort of heart and soul of the game is about confusing your opponents and having these layers of deception, so you need to have a kind of strategy that makes your opponent be uncertain about what cards you have.”

However, in her own life, Liv likes to show her hand. “I actually really try and take a policy of being as honest as possible in my social life, my business life and everything else. There's enough of a puzzle going on here [poker], so I don't need it in my real life - I want to keep that as simple as possible.”

Find out what Liv’s Poker Face tips are and more about how Dr Stengelin’s “trick or treat” experiments showed how children are good little liars by listening here.

More articles from Why Do We Do That?

-

![]()

Why do we laugh?

We may not all find the same things funny but all cultures in the world laugh

-

![]()

Why do we love dogs?

Dogs evolved from wolves but why did they choose us humans to be their best friends?

-

![]()

Why do we have grandmothers?

Ella Al-Shamahi finds out why a grandmothers role is so pivotal.

-

![]()

Six things that explain why we get upset when our football team loses

Why it's so devastating when our football team loses.