Spending time online has become a near-universal part of our daily routine. But something we perhaps don’t think about, is that when we check the ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ News homepage or watch our favourite show on iPlayer, that . Every page visit consumes a little electricity, and most of our global electricity comes from burning fossil fuels. In fact, the internet sector is responsible for more carbon emissions than the entire UK!

Our online activity uses energy in two main ways: first, through our devices, like laptops and phones, and second, through the shared internet infrastructure, like data centres and networks. The vast number of connected devices means that these are responsible for the lion’s share of internet energy use. If we want to reduce our online emissions, it is therefore essential that we get a handle on how devices consume energy while browsing the web and explore what we can do to mitigate this.

To address the need to reduce online emissions, various have been published for developers wishing to build low energy websites. The goal of such guidelines is laudable, but as for all sustainability efforts, it is important to ground recommendations in empirical data. In the absence of such data, guidelines may be inaccurate and lead to wasted developer effort implementing interventions that don’t work. To test some of the most common recommendations, we ran three simple experiments with a physical power monitor and two laptops.

Using dark mode

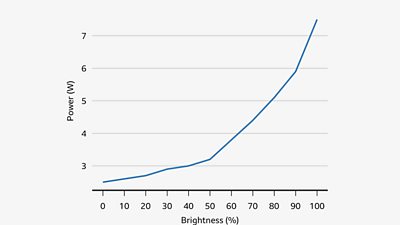

Dark mode is a popular dark-theme colour content scheme and research has found that, for some devices, switching to dark mode can reduce device power consumption. Energy conscious internet users are therefore encouraged to browse in dark mode. The catch is that the advertised energy savings haven’t been tested in the wild, where user behaviour can cause unexpected consequences.

To put dark mode to the test, we sat participants in front of the ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ Sounds home page and asked them to turn up the device brightness until they were comfortable with it. We repeated this for both light and dark mode versions of the Sounds page.

What we found was that 80% of our participants turned the brightness up significantly higher for the dark mode version. As shown in the figure above, increasing brightness increases energy use, and this pattern of user behaviour therefore results in a so-called 'rebound effect' which challenges the assumption that dark mode is the energy saving choice. Our in the recently concluded 1st International Workshop on Low Carbon Computing.

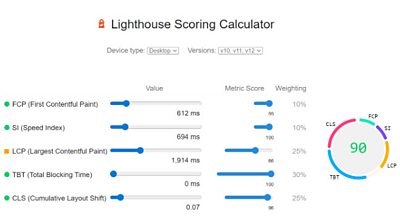

Optimising for performance

Faster websites are often more energy efficient, and consequently many energy optimisation recommendations simply mirror performance best practise. However, performance and energy efficiency aren’t always linked, so optimising for performance may not yield the desired energy results. We demonstrated this by measuring the score for a number of top websites and comparing this to their energy consumption. What we found was that there was no correlation at all between the two. Developers cannot therefore simply optimise for performance and hope that energy savings occur as a happy by-product.

Reducing data transfer

Perhaps the most widespread recommendation for decreasing browsing energy is to minimise the amount of data transferred over the internet. Data certainly has a relationship with online energy consumption and, broadly, decreasing data transfer is probably a good idea. Problems arise, however, when data is used as a direct proxy for energy. For example, estimate website energy use by converting gigabytes of data to kilowatt hours (kWh/GB). This provides a completely fictitious narrative of how emissions are generated on the internet. To prove this, we measured transferred data for the same set of top websites as before and compared this with energy consumption for those websites. We found only a low correlation between the two; evidence that data transfer is an inaccurate metric for estimating device energy. We further decided to test the latest , as this site features a 'Switch to Low Carbon Version' toggle, that claims to reduce data and emissions. We compared the energy of the 'full' version of the site with the 'low carbon' version and found that in some cases, the !

What can I do?

It doesn't all have to be doom and gloom. As a climate-conscious web user, there are a few simple things you can do to reduce your energy use.

Turning down the brightness on your phone or laptop, for example. A phone at full brightness might use twice as much power as one at low brightness! Keeping brightness to a minimum saves energy and has the added benefit of prolonging your battery life.

Switching to a smaller device could also save energy. For example, browsing on an external monitor connected to a laptop will consume more energy than browsing on a laptop alone, and browsing on a phone or tablet less energy still.

In addition to the cost associated with using devices, there is also an 'embodied' environmental cost for each device that has to be manufactured. This embodied cost is a combination of everything that goes into building a device, from mining the raw materials to the factories that put them together. Keeping your old devices for longer can help to reduce the number of new devices that need to be manufactured and therefore reduce our total emissions.

Next steps

With a few straightforward experiments, we have demonstrated that, as is common in sustainability, appealingly simple narratives give way to complexity when you scratch the surface. Online energy consumption is full of trade-offs, and there are rarely one-size-fits all solutions. Interventions that reduce energy in one scenario may not be effective in another. Web sustainability guidelines therefore need to be careful about the interventions they recommend and caution developers to think critically about the suitability of those interventions for their individual use cases. Moving forward, it is important we provide developers with tools that allow them to accurately estimate energy, so that they can verify their energy saving interventions have the desired outcome. To do so, we need a better understanding of what exactly causes our devices to consume energy when we spend time online.

That’s why at the ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ we are trying to model device emissions, so that we can develop evidence-based interventions that will allow us to reduce the overall footprint of digital media consumption, both internally and for the wider media industry. In that direction, we will continue working with the wider industry and share our findings to help advance digital sustainability best practices.

Contact the ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ Research & Development Sustainable Engineering team at sustainability@rd.bbc.co.uk.